THE ISLE OF LISMORE

(extracted from "Isle of Lismore" by Hector Macpherson,

M.A)

Location

| Lismore is a long narrow island, ten miles long

(including Musdile at the S. End) and not over 1½ miles broad.

It lies in the Firth of Lorn at the south end of Glenmore and shares

the S.W. and N.E. axis of the Great Glen. In the distance to the N.E.

Ben Nevis can be seen; on the westerly side rise the hills of Morven;

on the easterly the Benderloch hills with Glen Creran's mountains and

Ben Cruachan behind; and to the south the Firth stretches between Mull

and Kerrera with remoter views of Easdale and the Paps of Jura.

Some History

The first appearance of the island in history is

in 562 (or 563) A.D. when two Irish missionaries, Columba and

Moluag, arrived in the Firth of Lorn with some followers to find

a vantage point for Christian evangelism among the Picts and Scots.

The story goes that the two parties were nearing the shores of

Lismore when Moluag realised that his rival's coracle would beach

first. So great was his anxiety to claim this well-placed island,

that Moluag chopped off one of his fingers and flung it to the

shore, thus touching with his flesh the coveted land before Columba.

The now more famous saint turned wrathfully away, leaving Moluag

to his painful victory.

|  |

The name Lismore comes from lios ( a garden or enclosure)

and mor (large). Some say Lismore was called "the great garden"

on account of the fertility of its valleys and coastal strips;

others refer to the walled enclosure claimed by Moluag when he

set up his religious community at what is now called Clachan.

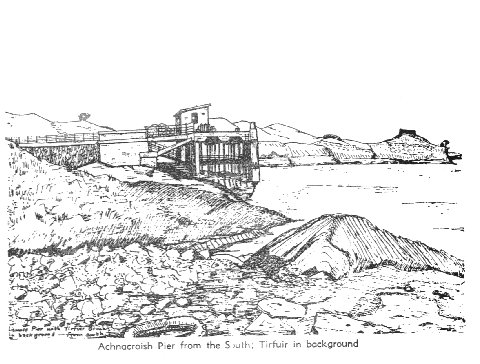

Before this time the island's name may have been Tirfuir, but

since Moluag it has been Lismore.

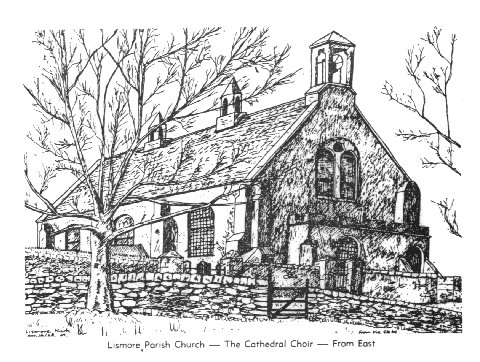

The Parish Church

|

Of Moluag's first church no trace remains. It may

have stood where the present one is, or at the highest point of

the present graveyard south of the Parish Church. In the 13th

century a cathedral was begun in stone; finished sometime in the

14th century. It appears to have consisted of choir/chancel

and nave, with a west end tower and a small chapel in the north

side of the chancel. The present church is the altered choir/chancel

in which can still be seen the mediaeval sedilia (clergy seats)

and piscina (basin for washing communion vessels). You enter nowadays

through the east wall where the high alter would have stood. Behind

the present communion table is the old choir and arch, and beyond

the vestry (modern) in the glebe, you can trace the outlines of

the nave walls and the foundations of the little tower at the

west end.

|

|

After the Reformation the choir was used as the Parish

Church - probably in poor repair - and the rest of the cathedral

fell into ruins. In 1749 the floor level was raised by about two

feet, the walls lowered by about nine feet and a new roof erected.

North, east and probably west galleries were required to seat

the worshippers (this was the Parish Church of Lismore, Appin,

Kingairloch etc!) and along communion table was placed along the

centre of the building, the pulpit being against the south wall.

Now only the east gallery remains, the pulpit faces east, and

a modern type of communion table stands in the now conventional

position.

Interesting Buildings

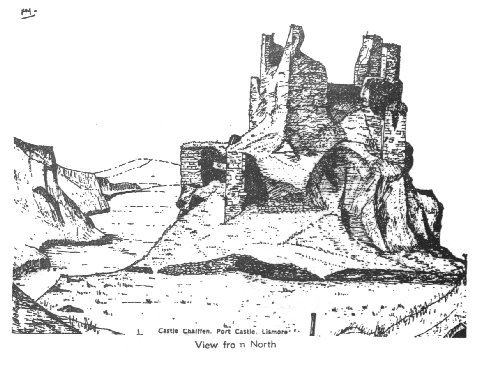

There are several other interesting buildings on

the island, the oldest being the pre-Christian "Pictish"

broch at Tirfuir (pronounced Tirry-foor) , one of a family of

Scottish brochs whose most famous member is at Mousa in Shetland.

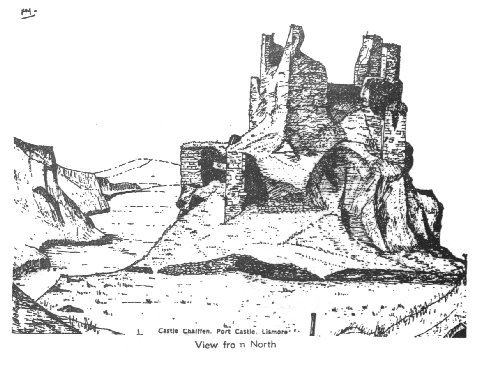

On the coast west of Clachan, at the tiny haven of Port Castle,

is Castle Coeffin (or Chaiffen), an old Viking fortress of the

period when Norsemen held all the northern and western isles of

Scotland. South of Achaduin (pronounced Achnadown) is the ruins

of the Bishop's Palace, a castle which was the mediaeval home

of the Bishops of Argyll and the Isles whose cathedral is the

present Parish Kirk.

|

|

|

Where the road to Achaduin leaves the road to Kilcheran

( pronounced Killie-cheeran - "ch" as in loch), there

stands, at what is now called Balligrundle, the old United Free

Church. This attractive little kirk was in use , in summer only,

until 1970, but it used to house an active congregation, the descendants

of the men and women of principle who left the Church of Scotland

at the Disruption of 1843. The principle for which they stood

has long been accepted and the breach healed; both the Church

of Scotland and the U.F. are one Presbyterian community. At Kilcheran,

next to the farmhouse, is a large house built as a Roman Catholic

seminary. Later it became a boarding house popular with visitors,

and now it is in private hands.

In the glebe, across the road from the Manse, is

a "standing stone". It was a marker of the mediaeval

sanctuary area where fugitives could seek ecclesiastical protection.

Nearly a mile N.E. of the Church on the N.W. side of the road

is a curious hollow in the limestone rock. This is "Saint

Moluag's Chair", where he used to sit in fine weather and

meditate. In the glebe, across the road from the Manse,

is a "standing stone". Two relics of the saint which

survive are his bell (in the National Museum of Antiquities in

Queen Street) and his pastoral staff, the Bachuil Mor. The family

of the Livingstones of Bachuil are hereditary keepers of the staff,

and the Bachuil is once more in their custody.

|

|

Two large and interesting homes are Achuaran House, near the north

end (Point), and Bachuil, almost a quarter of a mile north of

the Church.

PEOPLE AND WORK

In 1845 there were 1,430 people living in Lismore; in September

1971 there were 180; Yet the picture is brighter today than some

20 years ago. The drop in population has stopped and a slight

rise has begun. In August 1967 there were a dozen children in

the one-teacher school; today there are two teachers and a new

classroom added to cater for the roll of over 30 pupils.

This is a stable community, not like some rural ones to-day which

have become "dormitories" where people have their homes

but do not work, or shop, or go to school. Neither is it an exclusive

community as some insular ones can be; for, though most of the

residents are Lismore natives, several of the young men have married

girls from the mainland who have settled happily into the environment.

Gaelic is known by most of the people, though fewer families now

use it as the main language. There is no longer a Gaelic service

in the Kirk, and for some time the old tongue had not been heard

in the school. Happily, however, it is kept alive at ceilidhs

where old and young sing the lovely Gaelic songs, and once more

there are young entrants for the Mod.

A strong community feeling exists and is shown by much helpful

co-operation among farmers and housewives, and great willingness

to stand in for anyone ill or growing old. No one need ever be

lonely here. Entertainment and instruction are provided by a lively

badminton club, an intermittent drama group, evening classes at

the school, the Young Farmers' Association, the Woman's Guild

branch, and seasonal events such as clipping competitions, ploughing

matches, and Hallowe'en and Christmas parties.

A modernised and well-stocked shop which is also the Post Office,

is useful to residents and attractive to visitors.

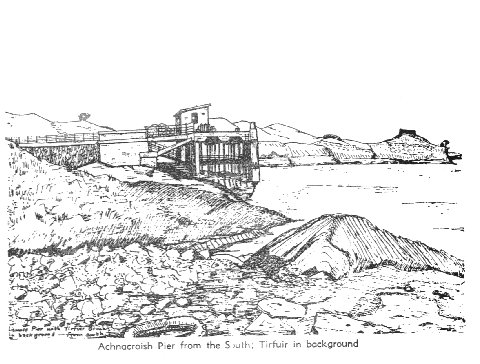

Lismore is linked with Oban and Port Appin. Twice daily, with

extra sailings on Monday and Friday, the 'Loch Toscaig" carried

passengers for a good number of years between Oban and Achnacroish.

In the autumn of 1973 the sturdy little vessel was replaced by

a new car ferry boat, the "Moivern", which, running

to the same timetable meantime, is the beginning of a long-awaited

car link, and should prove most useful to farmers especially.

A small passenger ferryboat crosses the narrow channel between

Point (Lismore) and Port Appin and by this route the doctor comes

to the island on his regular visits and on emergency calls.

A total of just under 12 miles of road on the island can be used

by cars. Some of the surface is fairly good and has been recently

much improved. Around forty vehicles use the roads, some being

tractors. Since no day-trippers can bring cars and since there

is no 'through road" to anywhere, this is an accident-free

area and there is safety for children and animals.

As mentioned earlier, all the people are farmers apart from retired

folk, the teachers, district nurse, shopkeeper, postman, minister,

etc. What a contrast with 1845 when there were bakers, cobblers,

millers, masons, joiners, lime workers, boat builders, fishermen

and coaster crews.' There are only one or two ponies on this island

where once fine grey and dappled horses were produced for export

and, according to the Rev. Gregor MacGregor, the inhabitants were

"famed for their skill as jockeys". Of course, when

there were over 1,000 people, there were inevitably some below

the poverty line; for the land could not carry so many in decent

comfort; but the drop in population has now gone too far, and

the danger always threatens with a pastoral economy that eventually

there will be too few folk to maintain a viable community with

school, church, shop and other needful amenities. Concentration

of industry and policies of centralisation have killed local industries

such as Lismore lime working, and slate quarrying at Ballachulish

and Easdale. And the remedy is not to set up, with Government

bait, branches of English or American spectacle makers or precision

instrument manufacturers' factories which bring no wealth to Highland

folk and will be closed at a breath of cold, economic draught.

The answer is, surely, the sponsored revival of native industries

such as lime, slate, and stone quarrying (we'd have better architecture

as a result!) and - above all - more help to established occupations

such as farming, forestry and fishing, e.g. in the shape of reduced

freight charges and better shipping services with assured rail

and road links.

Our Highland and Island way of life is a healthy and a good one,

and in the past it has produced some of our best men and women.

Scotland and the wider world cannot afford to let the spring dry

up from which such folk arise. Economic arguments for cutting

sea links, closing rural schools and churches, and thus raising

the burden of expense for folk in non-urban areas are of far less

importance than the need to put people before profits. A community

deprived of its best brains, its ambitions, its school, and its

Kirk loses its soul.

Lismore stepped into history as a centre for evangelism, a fountainhead

of a higher quality of life. Moluag lit a torch when he built

his church of wood and turf at Clachan. Perhaps we can still play

our part in showing that man does not live by bread alone . .

Lismore is peaceful, beautiful, interesting for the walker and

the nature lover. Its folk are friendly and hospitable. They welcome

visitors to explore the island to find peace and recreation here,

to join them in worship and in fellowship, and to fall under this

Island's ancient spell.

Tom Paterson

(last updated 2nd Jan 2021)